My Life (So Far) In Music

I must have heard music before I was born on November 1, 1945. My mother, Ruth Kronick, had a bachelor’s degree in music from Hamline University in St. Paul. I grew up hearing her play Chopin and Beethoven on the spinet piano in our living room. Now I have that piano in my music room.

My first instrument was a flutophone, a plastic wind instrument, which every kid played in the 4th-grade at Lenox School in St. Louis Park, Minnesota. In 5th grade, I moved on to a “real” instrument, the alto saxophone. By 8th grade, I was playing baritone sax in the St. Louis Park Junior High band. That’s when my love for jazz blossomed, in part inspired by the great baritone saxophonist Gerry Mulligan. It’s also when I learned the power of playing the lower notes of the musical scale — IT’S ALL ABOUT THAT BASS!

Richard Kronick (Photo by Andrea Canter)

After high school, the idea of being a professional musician seemed like an unreachable dream, and I decided to go for a B.A. in English. I attended Ohio University in Athens, Ohio, for two years. When I couldn’t afford to continue at OU, I came back home and enrolled at the University of Minnesota. I wrote reviews of jazz gigs for The Minnesota Daily, the U’s student newspaper.

Chris White

But I never lost my desire to play jazz. In 1966, I bought an electric bass and, in the spring of ‘67, I quit the University of Minnesota and moved to New York City. I had found Chris White’s ad in Downbeat Magazine offering bass lessons. Chris was a pro who had toured and recorded with Cecil Taylor, Nina Simone, Dizzy Gillespie, and other famous jazz musicians. However, because I was barely making ends meet in NYC as a clerk in a camera store, I could only afford a few lessons from Chris. I moved back to Minneapolis in the fall of ‘67 and enrolled once again at the University of Minnesota.

In 1968, while working as a clerk in a record store and then as a taxi driver, I played bass in a hippie band called Quick Grits with guitarists Chris Weber, Maurie Lazarus, and Paul Berget. They all played acoustic guitar and sang great three-part harmonies on folk-rock songs. Though Quick Grits only gigged regularly for a year or so, it has never stopped playing. It morphed into a jam group that has met in various living rooms and basements over the years. For the last 25 years or so, we have played in my basement. To this day, if I don’t have a gig on a Saturday night, chances are The Grits can be found in my basement playing blues and rock and having a great time. Maurie and I are still doing it, nowadays with Jeff Garetz on drums and Bert Black on keyboards. A previous member of Quick Grits once quipped that the band was “kind of like our Moose Lodge.” I figure we’re one of the oldest continuously existing bands in Minnesota history.

Quick Grits in the 1980s (L to R) Maurie Lazarus, Chris Weber, Jeff Klein, me, Soupy Shindler

Rahsaan Roland Kirk (1972 YouTube image)

The record shop I worked at in 1967 was called Music City. We were at the corner of 7th and Hennepin, the very center of Minneapolis’s downtown entertainment district. It was a fun place to work. One day, the famous hard bop jazz saxophonist Rahsaan Roland Kirk walked into the store. Kirk was blind. But instead of a standard white cane, he had the kind of bent-top wooden cane that physically disabled people use. Kirk’s cane was customized. Attached near the top with several wrappings of black electrical tape was an old squeeze-bulb automobile horn that he used to warn people to get out of the way. He had that kind of personality — very authoritative and gruff. Strapped onto the bottom of the cane with the same funky black tape was a wheel – a single caster. As he walked, he held the cane in front of him and warily rolled along. As he entered the store, he honked the horn and called out for help. Being a seasoned record store clerk and a serious jazz fan, I recognized Kirk right away. I was thrilled to meet this genuine jazz master. He said he wanted to know which of his albums we had on hand. I took him to the LP bin that had his name on it and dutifully read off the titles. He said, “Good!” and turned to leave the store. I wanted to continue the conversation with him — but I was at a loss for words. All I could think of to say was, “Mr. Kirk, which of your albums do you think I should buy?” He said, “All of ‘em!” and wheeled his way out of the store.

At about the same time, as a result of driving a taxi cab, I discovered The Cozy Bar in the heart of the North Minneapolis African-American ghetto. The Cozy was a blues and R&B club with a 99% black audience. It was exciting (and a little intimidating) to sometimes be the only white guy in the place. Muddy Waters, who by then was world-famous, played there regularly with his band. While the band played an opening set, Muddy would sit at the bar and drink whiskey. Once when I had had a drink or two and my courage was up, I walked up to Muddy and asked if I could sit in with his band. With no hesitation, Muddy said “Sure!” So there I was for one set, playing bass with Luther “Guitar Junior” Johnson, Otis Spann, and other guys whose records I had been listening to for years; it was one of the most exciting moments of my musical life.

In the spring of 1968, I married fellow English major Linda Oldefendt. I graduated with a B.A. in English and Theatre in 1970. Our daughter, Rachel, was born on December 11 of that year.

In the early 1970s, while working as a technical writer at Rosemount Inc., an engineering company, I was a member of one rock or blues band after another — more than I can count, some that I’d like to forget, and a few that never got off the ground. It’s hard to put a band together — and even harder to keep one together. Bands break up because everyone isn’t “on the same page.”

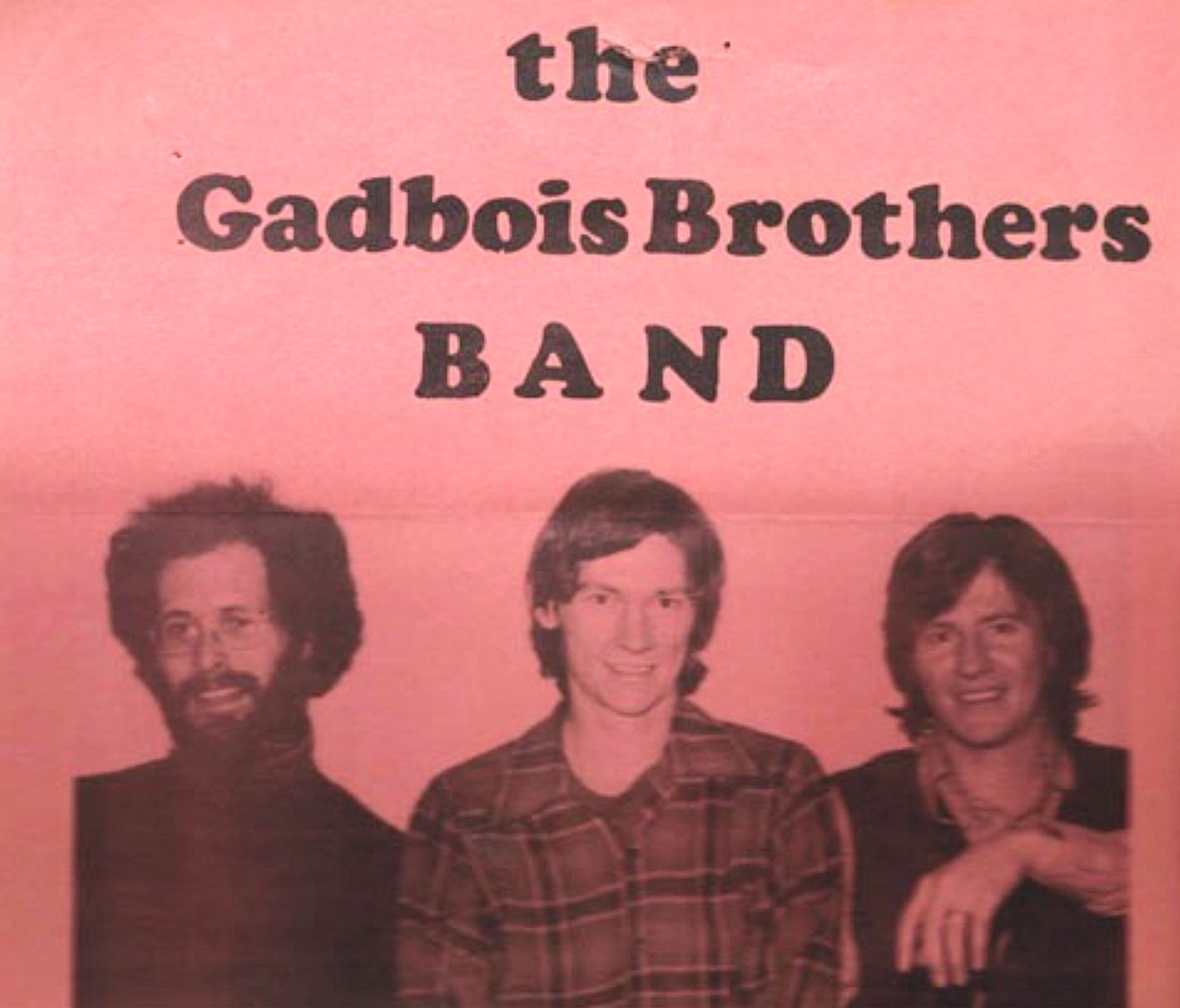

The Gadbois Bros. Band: Me, Nick, and Brett

In 1973, I joined The Jackelopes, a hippie jam band heavily influenced by The Grateful Dead. We played bars in Minnesota and Wisconsin. The Jackelopes were led by brothers Brett and Nick Gadbois. Brett played sax; Nick was on guitar. Both sang lead and backup. The group was rounded out by Matt Cook on pedal steel guitar (yes, our lead guitar was a pedal steel though we were not playing country & western — unorthodox) and Bill Niffenegger on drums. The band lasted about a year and then, with some personnel changes, we became The Gadbois Brothers’ Band, which played for another year or so, doing a mix of rock, R&B, and 1940s swing.

James Clute

In 1977, I was working as a technical writer for Boston Scientific, and I was bored stiff. I wanted to get serious about playing bass. Amazingly, I got permission from my wife (Thank you, Baby!) and from my boss to cut back to half time so I could study orchestral string bass. I began taking bi-weekly lessons -- first from Arthur Gold for a year, and then from James Clute for four more years. Both were members of the Minnesota Orchestra. Nearly every day, I devoted the two hours right after breakfast -- my most productive time -- to practicing for my lessons. It was sublime! I began to develop some proficiency playing with the bow and learned a lot about Classical music. Toward the end of those five years, I played in the Bloomington Civic Orchestra, had a few opportunities to perform chamber music, and began to dream of an orchestra career. But that’s when my music career took a turn.

Steamboat Willie

In 1980, while continuing my classical music lessons, I quit Boston Scientific and joined Steamboat Willie, a full-time country-rock band that had a house-band gig at Peabody’s, a big roadhouse in the St. Paul suburb of Inver Grove Heights. This was as close to musical fame as I have come. We played four nights a week for two years at Peabody’s. The band was composed of Donna Proctor, fiddle/lead vocal; Bill Carlson, guitar/vocals; Joe Tucker, pedal steel guitar/vocals; Steve Mack, piano/ vocals; me on electric and upright bass, and first Rex Berresford and later Dehl Gallagher on drums. At $400 per member per week, we may have been the best-paid band in the Twin Cities. Fueled by the Urban Cowboy craze, we played to a full house — about 1,700 people — every Friday and Saturday night. We had numerous fans and people asked for our autographs. When Peabody’s brought in big-time country acts like Mickey Gilley, Asleep At The Wheel, and Ricky Nelson, we were the perennial opening act. I’ll never forget meeting Ray Benson, leader of Asleep At The Wheel. On the afternoon of the concert, the owner of Peabody’s asked me to drive over to Ray’s hotel and fetch him to the club. When I knocked on the hotel room door, I heard his deep baritone voice saying “C’mon in!” Entering the room, I saw Ray sitting up on the bed. He’s about six-foot-six. His long legs, terminating in snakeskin cowboy boots, were sprawled on the bed. He was hitting on a thick marijuana joint. He offered me a puff, and we hung out for a while. Ray was totally relaxed and likeable. That was a fun day followed by an exciting concert at Peabody’s.

In 1981, Steamboat Willie was nominated for Best Country Band in the Minnesota Music Awards, though we didn’t win. In 1982, we went through some personnel changes and moved to a house-band gig at Cassidy’s On The Bluff, a bar in the St. Paul suburb of Lillydale, where we played for an additional year. When Steamboat Willie dissolved, I played for a year with a band called Gorgeous, led by guitarist/vocalist/songwriter Lonnie Knight. That four-year stretch in Steamboat Willie and Gorgeous was the last time I have been a full-time musician.

After playing music in a bar till 1 a.m., I would often hang out at The Rainbow Gallery, a counter-culture jazz club in Minneapolis owned by multi-instrumentalist Steve Kimmel. Steve had no liquor license, and The Rainbow Gallery catered to sober, serious jazz lovers. After the featured band of the night finished at around midnight, there was usually a second band that played until 3 a.m. I played a few gigs at The Rainbow Gallery with Eddie Berger and a band called Mary Ann’s Rainbow built around singer Mary Ann Hurst.

Meanwhile, in 1981, Linda gave birth to our twins, Jordan and Leah. With a family of five, I couldn’t afford to continue as a full-time musician — at least not with the money I was making. But I didn’t want to go back to being an employed tech writer. So in 1985, I took a big leap of faith and became a self-employed freelance writer, work that I continue to do today. That led to an offer to teach technical writing seminars, which took me around the world. Since 1986, I have taught more than 1,000 writing seminars in dozens of U.S. cities and in Canada, the UK, Ireland, Northern Ireland, The Netherlands, Germany, Australia, New Zealand, and Hong Kong.

The Red Gallagher Group

But I kept playing music whenever I could. In the mid-80s, I joined The Red Gallagher Group, which consisted of Red on guitar, harmonica, and vocals, me on bass and vocals, Ron Hines on keys, and either Tony Guscetti or Dehl Gallagher on drums. I still play with all those guys. Red moved to New Hampshire about 15 years ago, but he comes back to the Twin Cities for a month or more every year to play gigs.

Terry Burns

In 1996-97, I studied jazz bass with Terry Burns, who was then the head of the Bass Department at the McNally-Smith College of Music in St. Paul. I was not a student at the college; I took private lessons in Terry’s living room. I was dead-serious about this and practiced hours and hours for my lessons. Terry, who is an incredibly talented musician and a very smart man, taught me most of what I know about music theory and jazz bass. Just as valuable, Terry insisted that I read Effortless Mastery: Liberating The Master Musician Within by Kenny Werner. Kenny was and is a top-tier jazz pianist who has played on more than 100 records. Effortless Mastery, essentially a Zen Buddhist approach to being a musician, changed my life in deep and wonderful ways. It helped boost my self-confidence and showed me how to learn complex music methodically. I recommend the book to anyone serious about being a musician. So, as things turned out, it was only in my 50s that studying with Terry brought me to a level of real competence as a jazz bassist. In the dictionary, under “late bloomer,” there oughta be a picture of me.

For more experience reading jazz charts, I joined the Just Friends Big Band and played with them for 5 years. That led to stints with several other Twin Cities jazz big bands.

The original Chronic Quintet (L - R) Me, John Curlee, Maggie Roston, Tait Ferguson, Dehl Gallagher

In 2003, I met Maggie Roston at a Monday night jam at The Poodle Bar in Minneapolis. Soon afterwards, we formed The Chronic Quintet with Maggie on flute and sax, John Curlee (the lead trumpet in Just Friends) on trumpet and flugelhorn, Tait Ferguson on guitar, and Dehl Gallagher on drums. We landed a monthly gig playing jazz at Dixie’s On Grand, a New Orleans-flavored restaurant in St. Paul. Maggie moved to Buffalo, New York, a few years later, and there have been several other personnel changes in the Chronic Quintet. In 2009, I also joined Wild Honey, a band that plays Christian music in churches and secular funk and rock on club gigs. I continue playing in both bands today.

As I write this in 2021, I’m reminded of a radio interview of Bo Diddley that I heard when he was in his late 70s. The interviewer marveled at Bo’s long career and asked how long he intended to keep playing. Bo said, “I’m gonna keep doin’ it till Arthur comes for me.” Confused, the interviewer asked, “Who’s Arthur?” Bo said “Arthuritis!” I’m thinking the same way as Bo.

###